Verbal and written report made by his Excellency, General Petrus Stuyvesant concerning the occurrences and the affairs at the Esopus.

In conformity with the resolution we left in the private yachts on the 28th of May and arrived safely at the kil or river of the Esopes on the 29th. In order to avoid making any commotion among the Indians, either by surprising them by the sight of so many soldiers or by making them flee, before we had spoken with them, fearing also that during or before their flight they might inflict some more harm upon the small number of Christians, I had given orders to the accompanying yachts which carried most of the soldiers before arrival at the said kil, to follow separately at a distance and not to anchor near me before nightfall and not to show upon deck any soldiers or at least as few as possible. While we thus led in the yacht of Master Abraham Staats, ill luck would have it that in entering the kil at low water we ran aground. Meanwhile we sent Sr Govert Loockermans with the barge ashore, opposite to the two little houses of the Indians standing near the bank of the kil, to invite 2 or 3 Indians on board and dispatch one or two others inland for the farmers, so as to regulate my conduct according to their present condition. When he came back he brought with him two Indians and with them came Thomas Chambers and the precentor Andries vander Sluys, induced to come down to the river by the good south wind and the need for relief, which they had requested and expected. Their report and complaints agreed substantially with the letters previously sent to the honorable council; they added that the boldness and threats were still continuing and that they (i.e., the Indians) had since shot dead two pregnant sows of Jacob Jansen Hap near his lot. It would be too long, if it were possible, to repeat all the particulars, because they were given verbally, not in writing, and are therefore not all remembered. But a further detailing is unnecessary, because, as I said before, they agreed substantially with the letters previously sent.

I persuaded the Indians, brought along by Sr Loockermans, by a little present to go inland to their sachems or chiefs and inform them of my arrival, which was not to do them or the Indians in general any harm, but to inquire into the causes and who was guilty or not guilty of the quarrels, murders and arson: they were therefore to tell the sachems and Indians in the neighborhood that they need not be afraid, but that they should come to meet me and speak with me at the house of Jacob Jansen Stoll the following day or the day after, no harm should be done to them or theirs: they agreed to do it and after some further discussion went into the country with the aforesaid two Christians, viz, Tomas Chambers and Vander Sluys. The other yachts arrived in the meantime towards evening and passed by us, who were sitting aground. I ordered the Captain-Lieutenant to land the soldiers with muted drums, as quietly as possible, to keep them well together and after having landed them, to send for me and the people on my yacht. This was done by sunset. We marched on the same evening to the farm of Thomas Chambers, being the nearest, and remained there for the night. On the morning of the 30th being Ascension Day, we marched to the bouwery of Jacob Jansen Stol, which is the nearest to most of the habitations and plantations of the Indians, where we had appointed to meet the sachems and where on Sundays and the other usual feasts the scriptures are read. After this had been done on that day in the forenoon, the inhabitants, who had assembled there, were directed either to remain or to return in the afternoon, that they might report for our better information everything concerning the reasons of their request for assistance and hear from us, what they and we were to do.

When they had assembled in the afternoon, pursuant to orders, I stated to them, what they saw, namely that at their urgent and repeated requests I had come with the soldiers, numbering 60 men, and asked, what in their opinion was now best to do for the welfare of the country generally and for their own greater safety, adding in a few words, that I did not think the present time was favorable, to involve the whole country in a general war on account of a murder, the burning of two small houses and the other complaints about threats; that before now massacres, arson, sustained losses, injuries and insults had given us much more reason for immediate revenge, which nevertheless we had for prudence's sake deferred to a better time and opportunity and that, as they knew themselves, now, in summer, with the prospect of a good harvest before us, it was not the proper season to make bad worse, least of all by giving room so hastily to a blind fear; that on the other side they also knew very well, it was not in our power to protect them and other out-lying farmers, as long as they lived separately here and there and insisted upon it contrary to the orders of the Company and our well-intentioned exhortations. They answered that they had no objections to make, but they were now situated so that they had spent all they were worth on their lands, houses and cattle and that they would be poor, indigent and ruined men, if they were now again, as 2 or 3 years ago, obliged to leave their property. This would be the unavoidable consequence, if they could get no assistance and protection against the Indians. I told them then that no protection was possible, as long as they lived so separate from each other, that it would therefore be for their best and add to their own safety, in fact absolutely necessary, as I thought, that they should either immediately move together at a suitable place, where I could and would help and assist them with a few soldiers until further arrangements are made, or retreat to the Manhatans or Fort Orange with their wives, children, cattle and most easily-moved property, so as to prevent further massacres and mischiefs; else, if they could not make up their minds to either, but preferred to continue in such a precarious situation, they should not disturb us in the future with their reproaches and complaints. Each proposition was discussed, but it would be too tedious to repeat the debates in detail.

Everyone thought it unadvisable and too dangerous to remain in their present condition without the assistance and support of troops; the prospect of a good harvest, so close at hand, the only means, with which they are to clothe and feed themselves and their families during the coming winter, would not admit of abandoning so suitable and fertile lands and of throwing themselves and their families thereby into the most abject poverty.

The necessity of a concentrated settlement was conceded, although discussion ran high regarding this point as well as on account of the time, harvest being so near at hand and it being therefore thought impossible to transplant houses, barns and sheds before it, as on account of the place, where the settlement was to be made, for every one proposed his own place as being most convenienty located; to this must be added that they were to help in inclosing the settlement with palisades, which, they apprehended, could not be done before harvest time. Therefore they proposed and requested very urgently that the soldiers, whom I had brought up, might remain there till after the harvest, which we considered unadvisable for many reasons and therefore refused peremptorily, insisting upon it, as I did not want to lose time, that they should make up their minds without further delay in regard to one of the abovestated propositions and in order to encourage them to take the safest and most advantageous step, I promised them, to remain there and assist with my soldiers, until the place for the settlement was inclosed with palisades, provided they went to work immediately before taking up anything else and carried it out, whereupon they finally desired time for consideration until the next day, which I granted.

On the next day, which was the last of May, the aforesaid inhabitants of Esopus brought as answer that they had agreed unanimously and come to the conclusion to make a combined settlement, to acquiesce cheerfully and faithfully regarding the spot and arrangements, which we were to indicate and prescribe, and thy signed immediately the enclosed agreement;[1] the place was inspected and staked out the same forenoon.

I have forgotten to mention at the proper place that some Indians, but only a few, about 12 or 15, made their appearance at the house of Jacob Jansen Stol yesterday, but there were only two sachems or chiefs among them; they said that the other sachems and Indians could not come before the next day and that some were very much frightened and hardly dared to appear, because there were so many soldiers here and the report was that many more were to follow. After I had given them verbal promises and assured them that no harm should happen to them, they became a little more cheerful and satisfied and promised to communicate it to the other Indians the same evening, in consequence of which about 50 Indians, but few women and children among them, presented themselves at the house of the aforesaid Jacob Jansen in the afternoon. After they had gathered under a tree outside of the enclosure and about a stone's throw from the hedge, I went to them and as soon as we had sat down, they began according to their customs a long speech through their spokesman, which consisted, as the inhabitants interpreted it to me, of a relation of occurrences, which had happened before my time, especially of the war waged between them and our nation in Mr. Kieft's time, how many of their people had then been killed, which they had put away and forgotten and great many other things having no reference to the matter in hand. We answered, as was proper, that all this had taken place before my time and therefore did not concern me that they and the other Indians had drawn the war upon themselves by killing several Christians the particulars of which we would not repeat, because, when the peace was made, they had been forgotten and put away by us, (this is one of their customary expressions on such occasions); I had them asked by the interpreter, whether since the peace was made, or since my coming and remaining here, the least harm had been done to them or theirs. As they kept a profound silence, I stated to them through Jacob Jansen Stol and upbraided them for the murders, injuries and insults, which I then could remember and which they and other Indians had committed against our people during my administration, adding thereto finally what was still in everybody's memory, their latest proceedings in the Esopus, to discover the truth and the authors of which had induced me to come to the Esopus this time, without as yet having any desire to begin a general war, to punish or do harm and evil to any one, who was innocent of it, if the murderer would be surrendered and the damages for the burned houses paid. To convince them hereof still more, I added that we had not asked them, but they us, to come and settle on the Esopus that we did not own one foot of their land, for which we had not paid nor did we desire to own it, unless it was paid for.

I closed with the question, why then had they committed such murders, arson, killed hogs and did other injuries and continually threatened the inhabitants of the Esopus. For their vindication they had little to say, which was to the point, they hung their heads and looked upon the ground; finally one of the sachems stood up and said in reply that the Dutch sold the bisson, that is brandy, to the Indians and were consequently the cause that the Indians then became cacheus, that is crazy, mad or drunk and then committed outrages; that they, the chiefs, could not control the young men, who then were spoiling for fight; that the murder had not been committed by one of their tribe, but by a Neuwesinck Indian, who was now living at Haverstroo or thereabouts; that the Indian, who set fire to the houses, had run away and would henceforth not be permitted to cultivate his land. As far as they were concerned, they had done no evil, they were not angry nor did they desire or intend to fight, but they had no control over the young men. Whereupon I told them that if any of the young men present had a great desire to fight, they might come forward now, I would match man with man, or twenty against thirty, yes even forty, that it was now the proper tine for it, but it was not well done to plague, threaten and injure the farmers, their women and children, who could not fight. If they did not cease doing so in future, then we might find ourselves compelled in return to lay hands upon old and young, women and children, and try to recover the damages, which we had suffered, without regard to person. We could partly and easily do that now by killing them, capturing their wives and children, and destroying their corn and beans; I would not do it because I had told them and promised that I would do no harm to them now, but I hoped that they would reimburse the owner of the burned houses, arrest and surrender the murderer, if he came again to them and do no more evil in future. In closing the conference I stated and informed them of my decision that to prevent further harm being done to my people or brandy being sold to them, all my people should move to one place and live close by each other; that it would be the best, if they were to sell me the whole country of the Esopus and move inland or to some other place; that it was not good that they lived so near to the Swannekens, that is white men or Dutch, so that the cattle and hogs of the latter could not run anymore into the cornfields of the Indians and be killed by them and similar reasonings after the customs of the Indians to the same purpose, namely, that they ought to sell me all the land in that vicinity, as they had previously offered and asked us to do, which they took in further consideration as the day was sinking, and so we parted.

On the first of June we viewed and marked out the place for the settlement. The Indians came in the afternoon and their chiefs asked again through Jacob Jansen Stol and Thomas Chambers that I would not begin a war with them on account of the late occurrences, they promised not to do so again, as it had been done, while they were drunk and requested the abovementioned men to speak a good word for them to me. I went to the Indians with the aforesaid Indians, when they reported this, and they offered me a small present of about 6 or 7 fathoms of sewant, making thereby these two requests:

First, that they were most ashamed as well because of what had happened, but still more because I had challenged their young men and they had not dared to fight and that therefore they requested that nothing be said about this to others.

Second, that they have thrown away now all malice and evil intentions and would do no harm to anybody hereafter.

I ordered to give them in return a present of two lengths and two pieces of duffel, together about four yards, and told them that I too had thrown away my anger against their tribe in general, but that the Indian, who had killed the man, must be surrendered and that full satisfaction and restitution must be given to the man, whose houses were burned.

They answered in regard to the first demand that it was impossible, because he was a strange Indian, who did not live among them, but was roving about the country.

Concerning the second demand, namely, the payment for the fire, they thought that it should not be asked from the tribe in general, but from the party who had done it and was now a deserter and dared not return. As he had a house and land on the bank of the kil and had planted there some Indian corn, they thought that, if he did not return, this property ought to be attached; however, they said finally that satisfaction would be made for it.

Before parting I stated again to them that it was my will that my people should live close to each other for the reasons given before and that we had never taken nor would ever take anybody's land, therefore I asked them again to sell me the land, where the settlement was to be formed, which they promised to do.

On Monday, the 3rd of June, in the morning, I began with all the inhabitants and the soldiers of my command to dig out the moat, to cut palisades and haul them up in wagons. The spot marked out for the settlement has a circumference of about 210 rods and is well adapted by nature for defensive purposes. At the proper time when necessity requires it, it can be surrounded by water on three sides and it may be enlarged according to the conveniences and the requirements of the present and of future inhabitants, as the enclosed plan will show.

On the 4th of June I went to work again with all hands, inhabitants and soldiers. For the sake of carrying on the work with better order and greater speed I directed a party of soldiers under Sergeant Christiaen and some experienced woodcutters to go into the woods and to help load the palisades on the wagons, of which there were 6 or 7; the remaining men were divided again, one group of 20 under Captain-Lieutenant Newton, the other of like number under Sergeant Andries Lourensen, who were to sharpen the palisades at one end and put them up; the inhabitants, who were able to do it, were set to digging the moat and continued as long as the weather and rain permitted.

Towards evening about 40 or 50 Indians came to where we were at work, so that I ordered six men from each squad to look after their arms. After the working had been stopped they asked to speak to me and stated that they had agreed to give me the land, which I had desired to buy and on which the settlement was being made, in order to grease my feet, because I had made such a long journey to come and see them. At the same time they repeated their former promises that they would throw away all their evil intentions and that in the future none of them would do any harm to the Dutch, but that they would go hand in hand and arm in arm with them, meaning thereby that they would live like brothers. Whereupon I answered them appropriately that we would do the same, if they lived up to their promises.

On the 5th and 6th we continued our work and the Company's yacht arrived. As I found myself in need of several necessaries, especially gunpowder, of which we had not more than what was in the measures or bandoleers, nor had the yacht received more than two pounds for its own use, and as we were much in need of a few five and six inches planks for building a guardhouse and some carpenters to help us at our work first and then to assist the inhabitants in erecting their dwellinghouses. After the enclosure had been made, I concluded, in order to promote the one and the other, to go as quickly as possible on the Company's yacht to Fort Orange and was still more forced and encouraged to go by a good south-east wind, which blew all Thursday morning, and by a drizzling cold rain, which promised little prospect of progress for our work on that day.

On the morning of the 7th I arrived at Fort Orange, unexpected by everyone.

The yacht Gent did not arrive before the 8th, the tide running down so fast, and I shipped on her for account of the Company 160 hemlock boards, 100 five and six inch iron pins and an anker of brandy for the people working at the Esopus, as none had been put aboard or sent to me nor had I any for my own private use.

On the 9th was Pentecost.

On the afternoon of the 10th I left again after divine service and for brevity's sake and for other reasons pass over what happened there, as it has no relation to this subject.

I arrived again at the Esopus in the afternoon of the 12th and found everybody at his work and two sides completed. The wet and changeable weather had hindered the workers, as they unanimously declared.

On the 13t h, 14th and 15th we were busy making the east side and Fredrick Philipsen erected with the help of Claes de Ruyter and Tomas Chambers in the north-east corner of the enclosure a guardhouse for the soldiers, 23 feet long and 16 feet wide, made of boards, which had been cut during my absence.

The 16th was Sunday and after divine service I inspected with the inhabitants the land on the Esopus, which had not been purchased as yet, and found it suitable for about 50 bouweries.

On the 17th and 18th I had palisades put up on the north side. This was harder work, because this side could not be made as straight as the others, which the plan will show.

Four carpenters came also on the 18t h, engaged by Mrs. de Hulter to remove her house, barns and haybarracks and on the 19th three more, whom I had asked and engaged at Fort Orange to make a bridge over the kil. They were also to help the others remove their buildings, for which they had asked me before my departure for Fort Orange.

Further, as the inhabitants were still hauling palisades with their wagons and horses and therefore not yet ready to employ the carpenters immediately and as I had given them a promise at Fort Orange that they should be employed immediately or else receive free return transportation and daily wages besides; therefore, I resolved to have them square some timber for a small house or barn at my own expense; the ridge of it was to lie on two beams and the people, who could not move their houses so quickly, were at first to be lodged there and afterwards I thought to use it according to circumstances as a wagon shed or stable for horses and cows, for I had long intended to begin the cultivation of my bouweries in the Esopus, incited thereto by the fertility of the soil, but prevented so far by the audacity of the Indians and because the people were so scattered. The last objection having now been removed and thereby, as I hoped, also the first one, I took the aforesaid resolution principally to encourage the good inhabitants, by risking my own property together with theirs, to make the settlement and cultivate the ground and to fulfill my former promise, although I was not obliged to do it at present nor would be in a year or two. Therefore the building is made as small and plain as possible, for I thought more of employing the carpenters, who had come there at my request, and of the convenience of the people, than of my own advantage. When the timber had been squared and brought to the spot, my carpenter and others told me that it would make only a little difference in the costs, if I had a small barn of 5 or 6 bents[2] made, in case the ridge was laid on two beams, as I said before. I referred the carpenter's work to the opinion of my carpenter, Fredrick Philipsen.

About noon of the 20th the sides of the stockade were completed and it was only necessary, to stop up a few apertures where roots of trees had been in the ground. This was accomplished in good time on that day.

We might have marched on the 21st or 22nd, but the wind was unfavorable and I let the men rest; some helped in breaking down and removing the houses of Thomas Chamber and Jacob Jansen Stol and put up six bents for the aforesaid barn.

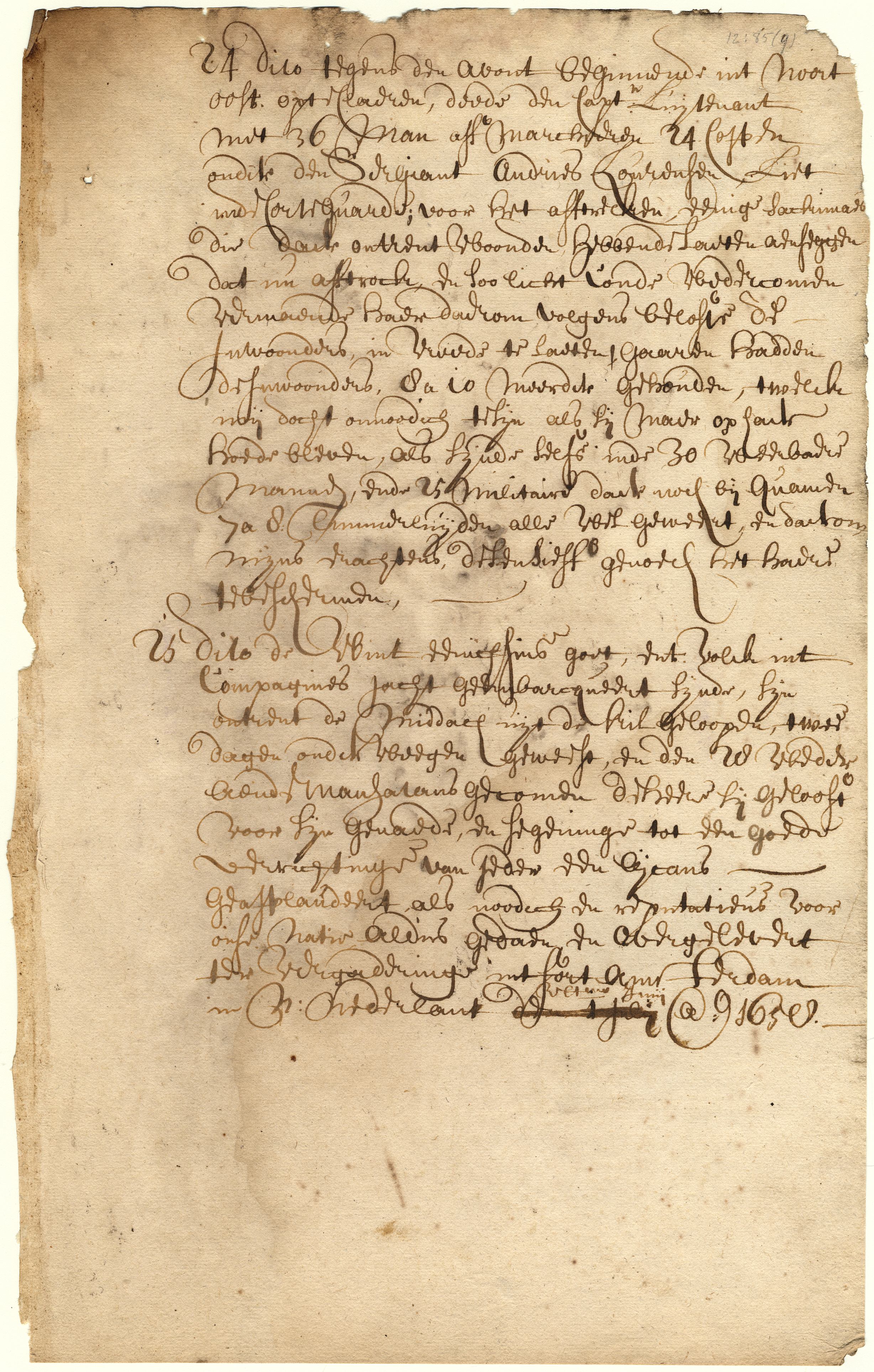

Towards evening of the 24th it began to clear up in the northeast and I ordered the Captain-Lieutenant to march off with 36 men, leaving 24 men under Sergeant Andries Lourensen in the guardhouse; before departing myself I had some of the sachems, who live near there, informed of my departure, but that I could easily return; I reminded them that, pursuant to their promises, they must leave the inhabitants in peace. The inhabitants would have liked to keep 8 or 10 soldiers more, but I did not consider it necessary, if they would only be on their guard, for they count themselves 30 fighting men, besides the 25 soldiers and 7 or 8 carpenters, who too are well-armed. They are therefore, in my opinion, perfectly able to protect themselves.

On the 25th, about noon, we left the kil, the wind being fair and the soldiers embarked on the Company's yacht; we were two days coming down and arrived at the Manhatans on the 25th. The Lord be praised for His mercy and blessings on the successful execution of a matter, which almost everyone applauded, as being necessary and honorable to our nation.

Thus done and delivered at the meeting of the council at Fort Amsterdam in N. Netherland, the last of June 1658.

Rights: This translation is provided for education and research purposes, courtesy of the New York State Library Manuscripts and Special Collections, Mutual Cultural Heritage Project. Rights may be reserved. Responsibility for securing permissions to distribute, publish, reproduce or other use rest with the user. For additional information see our Copyright and Use Statement Source:New York State Archives. New York (Colony). Council. Dutch colonial administrative correspondence, 1646-1664. Series A1810-78. Volume 12, document 85, page 1, side 1.